Charles Waite Wadsworth – The Silent Service

When Charles Waite Wadsworth stepped aboard the USS Tang in Sept, 1944, he would have been well aware that the Balao-class submarine was already the most decorated boat of the war, and one of the most prolific in submarine history. Commissioned just one year earlier on October 15, 1943, the Tang was being prepared for its fifth mission in the Pacific, this time headed to the Formosa Straight under the leadership of its first and only captain, Dick O’Kane.

O’Kane was considered one of the most brilliant sub captains of the war, having set a single mission record sinking of more than 39,000 tons of Japanese ships in its third mission. But this mission would push even the maverick O’Kane into the most dangerous area in the Pacific, where there was little room for maneuvering between two highly traveled, but heavily protected shorelines in relatively shallow waters. For O’Kane and the crew of the Tang, however, the reward of a sea potentially full of Japanese ships meant easy pickings, and a quick return to the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in California. For Charles, part of a hand-picked crew of only the best men in the Navy, a successful mission meant returning to his California home for an extended shore leave.

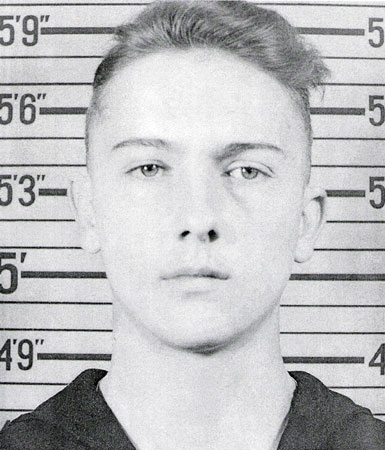

Charles Wadsworth, Torpedomans Mate Third Class, was just 19 years old when he was assigned to the Tang for its fifth mission. Born April 29, 1925, Charles, the youngest child of Harry Leland Wadsworth, and Helen Elizabeth Waite was born in Los Angeles and until his enlistment in the Navy, lived in North Hollywood, California with his older sister Sarah.

The American Submarine Force is an all volunteer group and any candidate that passed the rigors of submarine school was well prepared to join the Silent Hunters of World War II. Charles would have been well aware of the hazardous nature of the assignment, nearly 20 percent of the submariners went down with their ship. Perhaps Charles felt, like another of his time, that he wanted to come back whole, or not at all. For Charles, this would be his first mission, and his last.

After leaving port in late September, the Tang quickly slipped beneath the Pacific waves just south of Pearl Harbor where it had been in port for the previous weeks. Shortly after getting underway, Operations Orders were posted, giving the crew the first inkling of what lie ahead. After heading to Midway for refueling, the boat was to sail off the coast of Formosa, down the Strait that separated the island from the mainland of coastal China. The Formosa Strait was an important military supply route between Japan to the Philippines. Protected from the open ocean, the narrow strait was often shallow, leaving little room for submarines to hide when performing evasive maneuvers.

Word came on October 22, 1944, that a convoy of ships consisting of three tankers, one transport, and one freighter, along with several escort ships, was detected moving down the strait. Early the next morning, the crew of the Tang began firing torpedoes, sinking five ships.

In less than 24 hours, another convoy of ships appeared on the radar screen. Five ships, transports and tankers, were hit with 10 of the Tang’s supply of 24 Mark-18 torpedoes. With only two left, the men could certainly feel that a well deserved trip home was soon within their grasp. The last two torpedoes were pulled from their tubes and examined, then returned to the ready. Meanwhile a stricken transport was waiting above, and Captain O’Kane was determined to finish her off. There could be no mistakes.

The Tang pulled to within 900 yards of the ship and fired one of its remaining torpedoes. The phosphorescent wake showed that it was headed “hot, straight, and normal.” Now only one torpedo stood between one of the most successful submarine missions of the war, and a trip to home and safety for the men of the USS Tang.

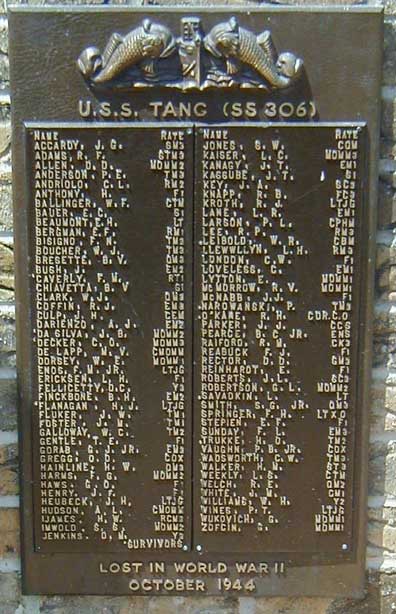

O’Kane gave the command to fire, and the final torpedo left its tube, headed straight for the wounded ship. Torpedo 23 hit its target, sinking the 6,957 ton Ebaru Maru while the final torpedo was still on its way. On the bridge, the Captain and Chief Boatswains Mate Bill Leibold saw number 24 breach the surface and begin to turn in an arc back toward the Tang. O’Kane ordered full power to try to avoid the circling torpedo, but within minutes, it struck the port side near the torpedo room, killing all near the point of impact instantly, probably including Charles Waite Wadsworth.

The Silent Service, those brave men who risked their lives beneath the waves of the Pacific during World War II, did so without the recognition usually reserved for those who fought more publicly, but no less valiantly, on the beaches and front lines of Pacific island battles. I first came across the name Charles Waite Wadsworth when visiting a Pearl Harbor memorial to lost submarines. Engraved in bronze, the names of the 74 men lost, are men who rest silently, but are not forgotten.

This was my Dad’s cousin.

Loring(Spike) Lyman Wadsworth decorated Army Ranger from Point Du Hoc/D-day.

Featured in the Book Rudder’s Rangers : The True Story of the 2nd Ranger Battalion D-Day Combat Action and honored by Ronald Reagan at Normandy convention. Also spoke on behalf of rangers at republican convention(video taped).